Austin experienced its warmest meteorological fall on record, which includes September, October, and November. 75.8°F was the recorded average temperature including the highs and lows for each day. This fall was also abnormally dry, only receiving 2.6 inches of rain compared to the average of 10.3 inches. Most of the rainfall took place in November despite October usually being the region’s second wettest month of the year. Aquifer levels continued to decline amongst these dry and warm conditions.

Rainfall

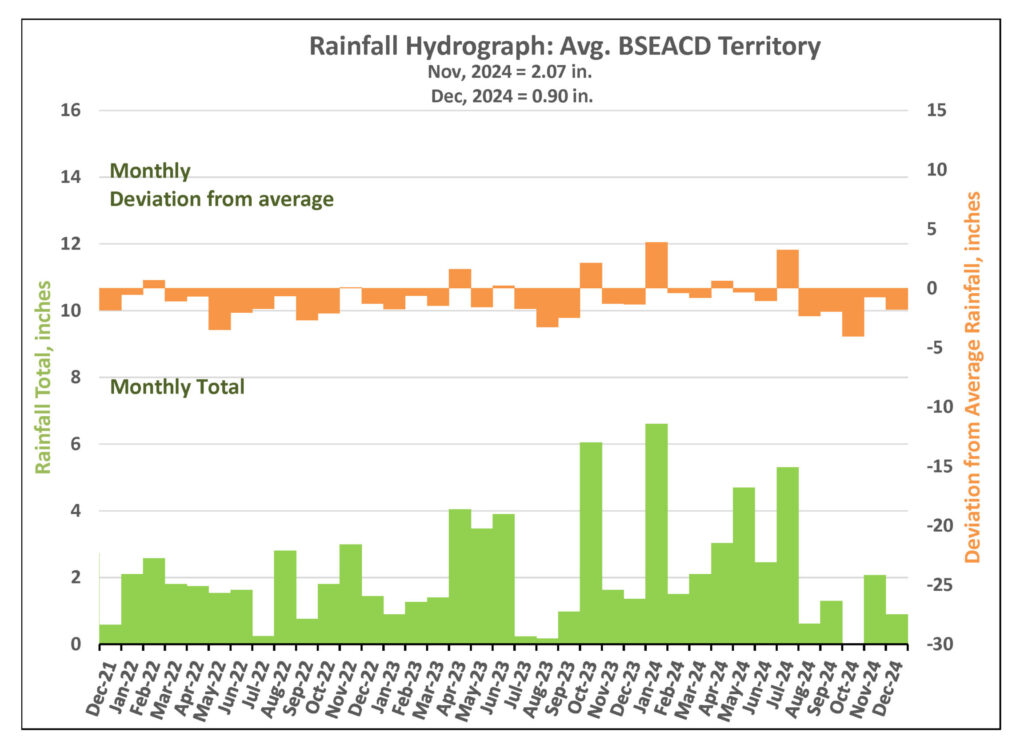

November, typically our seventh wettest month with an average rainfall of 2.8 inches, brought 2.1 inches of precipitation to the Hill Country—a notable contrast to the unusually warm and dry October (Figure 1). From January through November, the region has received an average of 29.6 inches of rain, falling 4 inches short of the typical average for this period. So far through December we’ve received 0.9 inches of rain, and we’ll need another 1.8 inches to get to the monthly average.

Figure 1. Monthly deviation from average and monthly total rainfall in District’s territory.

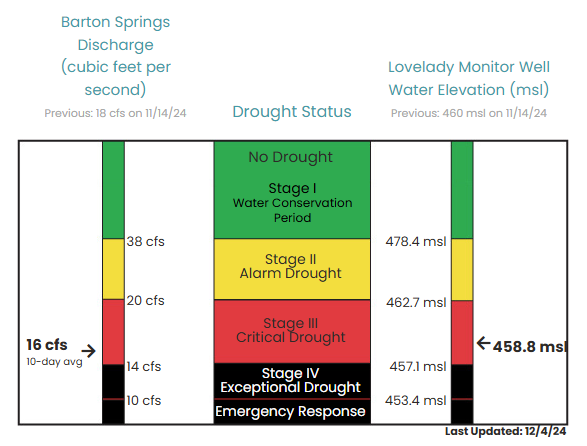

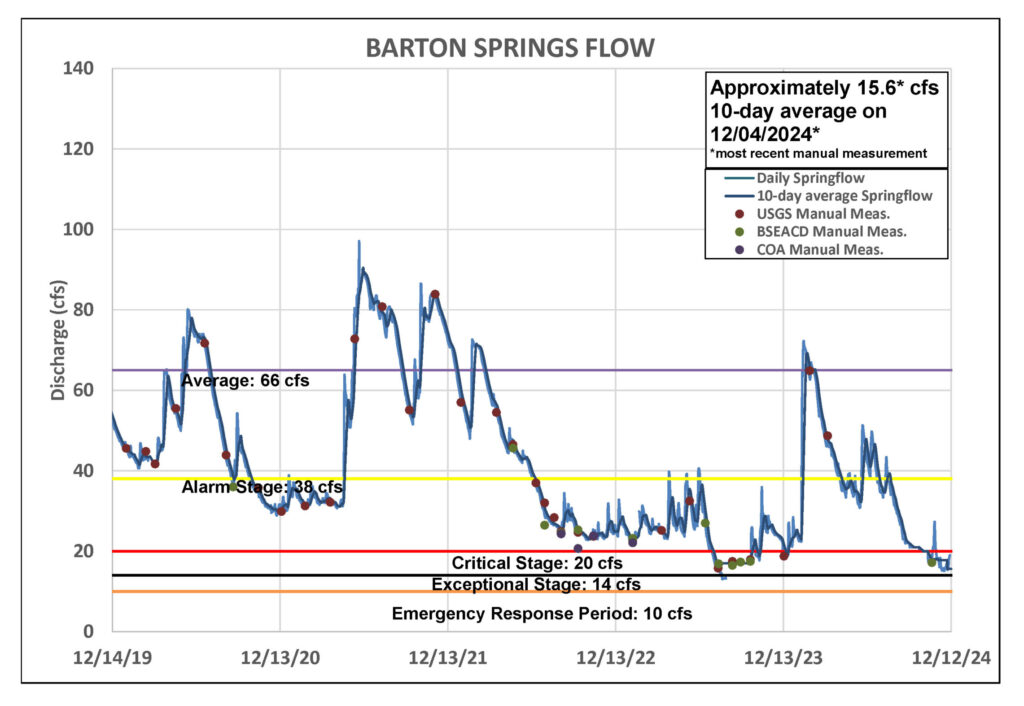

Drought Triggers and Status

The District remains in Stage III Critical Drought at this time. You see Barton Springs flow and Lovelady groundwater levels by visiting www.bseacd.org/drought-status.

Barton Springs Flow

As of December 4, the 10-day average flow at Barton Springs is 16 cubic feet per second (cfs) (Figure 2). Recent maintenance and spillway operations have affected pool levels, potentially impacting the accuracy of the USGS real-time gauge. To ensure accuracy, manual measurements have been conducted, with the most recent on December 4 confirming a flow of 16 cfs. While this aligns with the USGS reading, it hovers near the Stage IV Exceptional Drought threshold of 14 cfs. The next manual measurement is scheduled for December 18.

Figure 2. Barton Springs flow for the last five years.

Lovelady Monitor Well

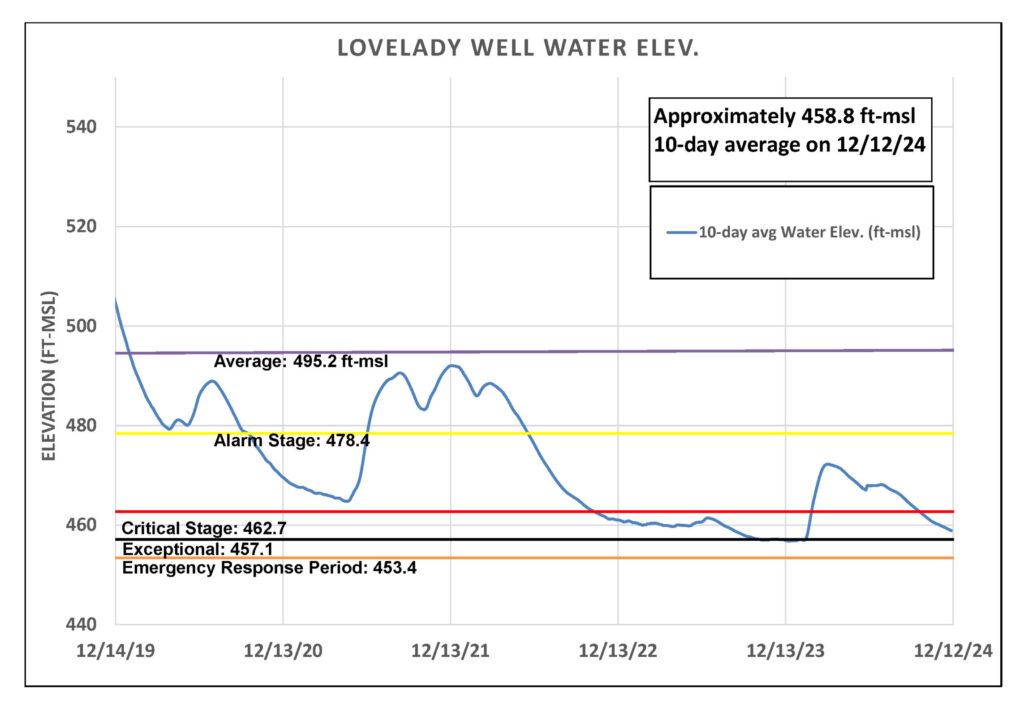

As of December 11, the 10-day average water level at the Lovelady monitor well was recorded at 458.8 feet above mean sea level (ft-msl), placing it within the District’s Stage III threshold and approximately 1.7 feet above the Stage IV Exceptional Drought threshold (Figure 3). Without rain we could see water levels at Lovelady dip into Stage IV as soon as February.

Figure 3. Lovelady groundwater level over the last five years.

Trinity Aquifer

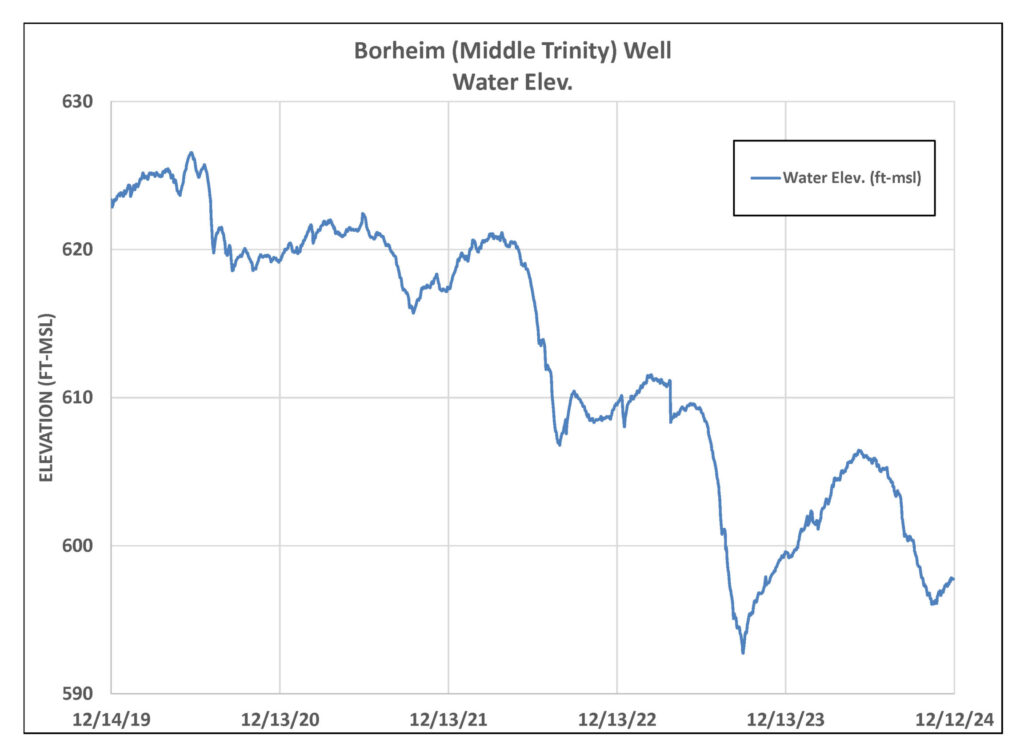

The water level in the Borheim Middle Trinity monitor well, located between Buda and Driftwood, had been steadily declining since late May 2024. However, early November rains reversed this trend, raising the water level by approximately two feet. Levels could continue increasing with additional rainfall in December (figure 4).

Jacob’s Well Spring (JWS) showed a minimal response to the November rains, with a flow increase of less than 1 cfs and some additional flow observed following December rainfall. Meanwhile the Blanco River at Wimberley gauge peaked at 62 cfs during the November storm surge but has since receded to a current flow range of 6 to 7 cfs.

Figure 4. Borheim (Middle Trinity) monitor well water-level elevation.

Conservation: Rain Gardens

You might notice yards with gardens that dip slightly into the landscape and have various native species planted within. These are called “rain gardens”, and they are designed to boost soil’s ability to absorb runoff from surfaces like roofs, sidewalks, and driveways.

With more development taking place throughout the Hill Country, natural landscapes are being replaced with surfaces that are impervious, such as concrete, pavement, and even compacted soil. Impervious means to “not allow liquid to pass through”, so these surfaces prevent water from penetrating the soil and recharging aquifers that may reside below. Water that hits impervious surfaces becomes runoff and results in more severe erosion and flooding in our already flood-prone region. Even turfgrass yards aren’t ideal for maximizing the absorption of precipitation.

Rain gardens help create more pervious (or permeable) surfaces and allow additional water to soak into the ground. Many of them have rain barrels that feed directly to the garden. These sites are designed to be slightly depressed into the ground, which allows them to capture more water and let it slowly soak into the ground. The native plants in the garden help hold the soil in place and filter out pollutants while also benefiting from the extra moisture. By reducing the quantity of water that runs off, rain gardens help lower the risk of flooding and erosion in our communities.

To learn more, explore these helpful articles:

- Soak Up the Rain: Rain Gardens –EPA

- Rain Gardens Keeping Water on the Land – City of Austin

- Rain Gardens – NOAA