You might have seen recent stories saying Travis County is drought-free for the first time in two years. If this is the case, then why is the District still in Stage II Alarm Drought?

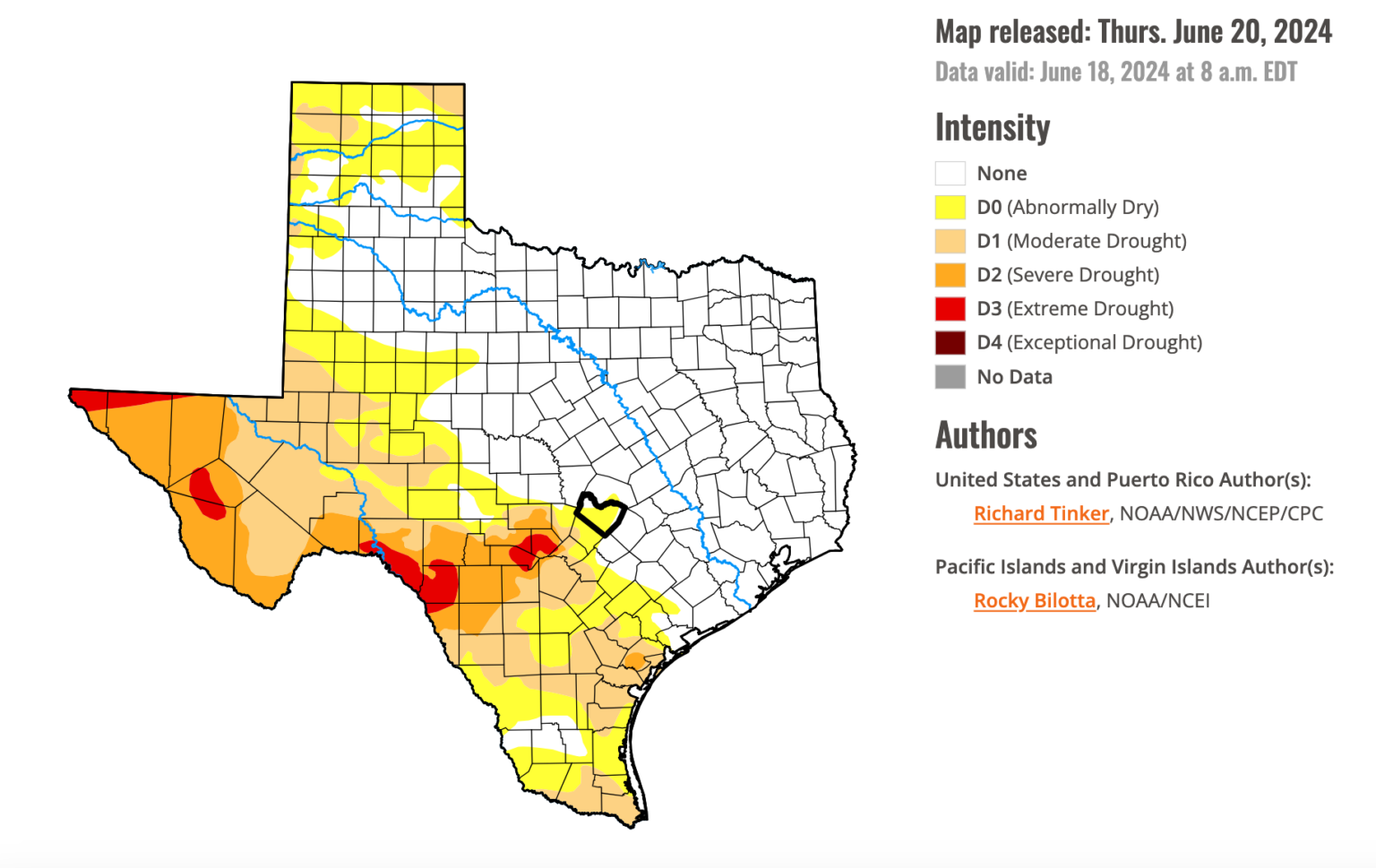

As of June 20, the US Drought Monitor shows Travis County (outlined in black) is out of drought and listed as ‘Abnormally Dry.’

Current Conditions in the District

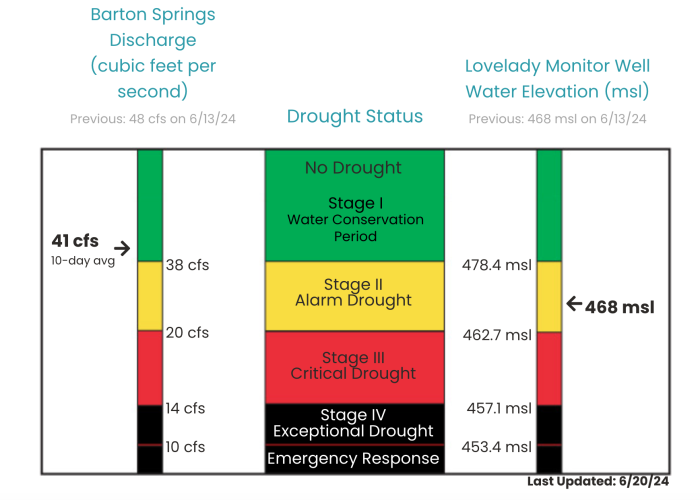

This year the District has received approximately 20.1 inches of rainfall from January – June. This is more than the area received in the same time frame last year (15 inches) and also above the historical average for the first half the year (18.5 inches). Barton Springs flow, one of the District’s two drought sentinels, is at a 10-day average of 41 cubic feet per second (cfs), which is within the ‘No Drought’ – water conservation threshold.

Even so, the District continues to feel the lasting impacts of the drought that started two years ago. Despite above average rainfall this year, it hasn’t been enough for groundwater levels to fully recover to pre-drought levels. Lovelady monitor well is the District’s other drought sentinel, and its water level is at a 10-day average of 468 feet-mean sea level (ft-msl) and remains within Stage II drought.

Different Types of Drought

Drought is defined as “a period of drier-than-normal conditions that result in water-related problems”, and there are several varieties of drought. The kind most people are familiar with is meteorological drought—a rainfall deficit affecting the landscape. Over time the lack of rain produces agricultural and also hydrological droughts. Droughts that affect the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer and the Trinity Aquifer can be best characterized as hydrological, and even more specifically, groundwater droughts.

The US Drought Monitor, which shows Travis County is out of drought, takes a variety of factors into consideration including “precipitation, streamflow, reservoir levels, temperature and evaporative demand, soil moisture and vegetation health.” While it’s representative of many drought factors, this monitor tends to lack in its consideration of groundwater levels, which is the District’s primary focus.

Groundwater droughts often have a time-lag response to periods of high or low rainfall. The District utilizes flow from Barton Springs and water levels in the Lovelady monitor well to indicate drought status of the aquifers. Barton Springs flow is a good measure of the overall health of the aquifer system. However, like a stream, Barton Springs can be highly sensitive to minor and localized rainfall events. Conversely, the Lovelady well has muted responses to rainfall, but is a good measure of overall storage of groundwater in the aquifer.

Getting the District Out of Drought

For the District to declare drought conditions, either Barton Springs flow or the Lovelady water levels need to be below their respective drought thresholds. However, to exit a drought stage, both drought sentinels must rise above their respective drought trigger values. This is why the District remains in Stage II Alarm Drought at this time.

A Dry Forecast

Unfortunately, the forecasts for our area are looking pretty dry. The District is in its 24th month of continuous drought, and July and August are some the area’s driest months of the year. The National Oceanic Atmospheric Association (NOAA) expects El Niño to neutralize and switch to La Niña conditions by late summer, which usually brings drier-than-average conditions and above-average temperatures to the southern United States. La Niña is forecasted to last until February 2025. With aquifer levels already in Stage II Alarm Drought and continuing to decline, it is paramount that we practice proper conservation techniques to brace for continued hydrological drought and descending back into meteorological drought again.