Beneath the rolling landscape of the Texas Hill Country lies thousands of caves, which play an important role in recharging local groundwater resources. The Edwards and Trinity aquifers, portions of which the District manages, are karst aquifers. These form from the gradual dissolution of soluble rock, like limestone. This process of dissolving away the rock results in passageways including caves, sinkholes, and cracks throughout the landscape. Precipitation runoff then enters these features to become groundwater.

The Significance of Antioch Cave

Antioch Cave lies within the creekbed of Onion Creek and is located just over a mile from downtown Buda. It gets its name from the Antioch Colony—a rural farming community of Black freed people formed during the Reconstruction Era in the 1860’s. Onion Creek is the main contributor of recharge to the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer, providing an estimated 45% of total recharge. Antioch Cave accounts for the largest amount of recharge of any of the discreet recharge features on this creek.

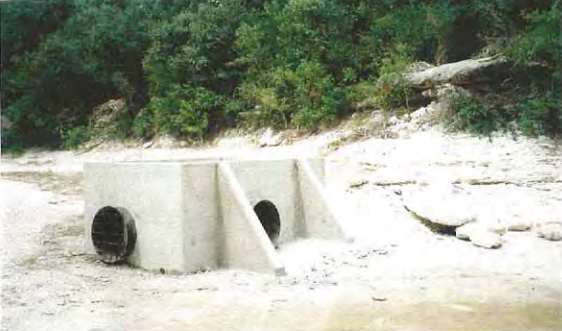

Entrance to Antioch Cave before the structure was constructed over it. Photo from Fieseler, 1998.

During flooding events, large amounts of water can enter Antioch Cave and recharge the aquifers below. These times of high flow also mean there’s potential for surface pollutants (sediment, bacteria, nutrients, etc.) to enter and contaminate groundwater.

The Edwards Aquifer and underlying Trinity Aquifer provide drinking water for tens of thousands of people. The Edwards Aquifer is also the water source for Barton Springs— critical habitat for two local endangered salamander species. Because of this, it’s important that the District monitors and, when possible, manages the quality of water recharging the aquifer. During the earlier stages of a major rain event, flood water flushed into Onion Creek is more concentrated with contaminants and sediment. To prevent large amounts of these pollutants from entering the aquifer while still allowing higher quality water to enter Antioch Cave, the District has implemented an innovative project at this site over the last several decades.

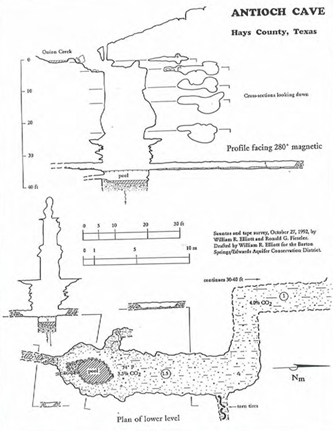

Map of Antioch Cave, which was produced after the initial explorations of the cave in 1991 and 1992. Photo from Fieseler, 1998.

Implemented Projects to Protect Recharge

Made possible by a grant through the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the District installed a concrete vault over Antioch Cave in 1997 as seen below. The structure included two valves that could be open and closed manually. Water quality was determined by staff through visual observations and measurements of turbidity — how murky the water was. This gave the District the ability to close the valve and prevent contaminated water with high turbidity from entering the cave and aquifer at this site.

The near-finished vault over Antioch Cave as featured in Fieseler, 1998.

Schematic cross section across Onion Creek and Antioch structure looking upstream as featured in Smith, 2011.

In 2008, after receiving additional funds from the EPA, modifications were made to the structure over Antioch Cave. An automated valve, along with pipe and screen, was installed. This valve is connected to a nearby water quality probe and operates based on real-time readings, opening and closing as needed. This additional valve not only increases the amount of recharge entering the cave but also improves efficiency. The automated system is designed to close the valve when contamination levels in Onion Creek exceed a certain threshold. This typically occurs during the first flush of stormwater runoff from nearby urban areas, such as roadways. The mechanism helps prevent pollutants from entering Antioch Cave and the Edwards Aquifer. Once contamination levels drop below our required threshold, the valve reopens automatically and allows stormwater to enter the cave and become groundwater.

Concrete structure over Antioch Cave in January 2025.

Antioch structure under water with a whirlpool nearby during a flooding event in 2001.

Efficacy of Project

While the District has not run a continuous study on the impact of the Antioch structure since it’s installation, research was conducted in 2010 that reviewed five storm events. This study estimated over 2,400 pounds of nitrogen from nitrate/nitrite, nearly 300 pounds of phosphorus, and more than 190,400 pounds of sediment were prevented from entering Antioch Cave. For reference, this amount of sediment is equivalent to eight dump-truck loads.

Sources Referenced in this Article

- Implementation of Best Management Practice to Reduce Nonpoint Source Loadings to Onion Creek Recharge Features – Ronald Fieseler, 1998

- Fieldtrip Guidebook Recharge and Discharge Features of the Edwards and Trinity Aquifers, Central Texas – Brian Smith, Robin Gary, and Brian Hunt, 2009

- Final Report for the Onion Creek Recharge Project Northern Hays County, Texas – Brian Smith, Brian Hunt, and Joseph Beery – 2011

- Recharge and Water-Quality Controls for a Karst Aquifer in Central Texas – Brian Smith and Brian Hunt, 2018

- Final Habitat Conservation Plan for Managed Groundwater Withdrawals from the Barton Springs Segment of the Edwards Aquifer – Barton Springs-Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, 2018

- Buda History – The Antioch Colony – City of Buda, 2018

- Caves: A Window into the Edwards Aquifer – The University of Texas at Austin